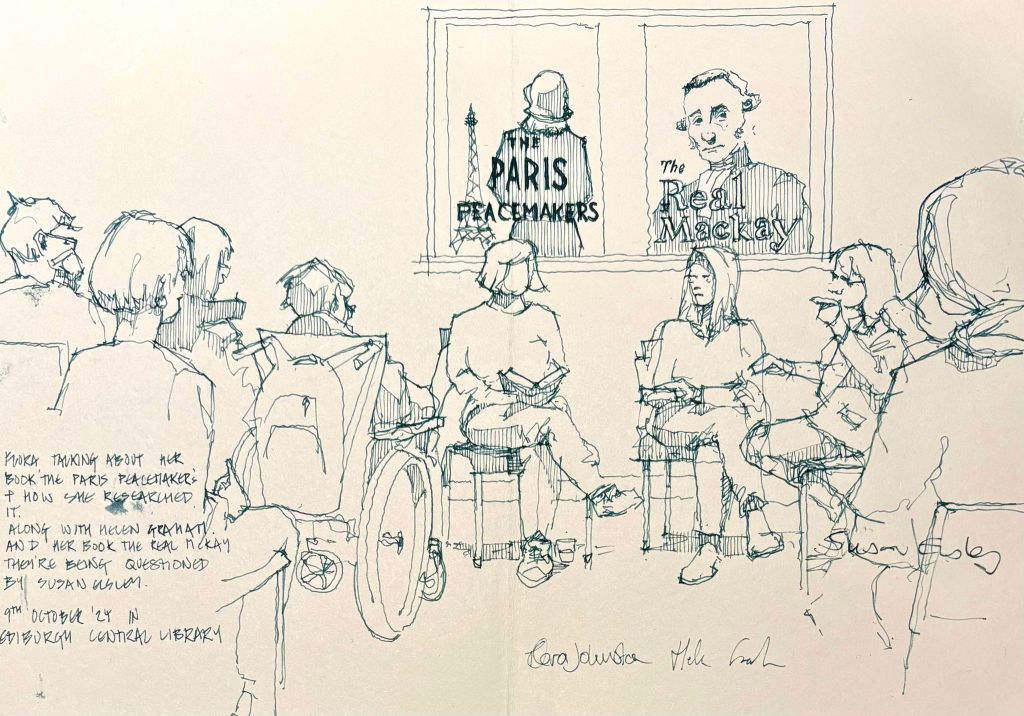

Canadian National War Memorial at Vimy Ridge

Extracts from War Classics: the remarkable memoir of Scottish scholar Christina Keith on the Western Front, ed. Flora Johnston

Then we came to open country and the road wound upwards. Stretches of barbed wire, gashes in the ground, trails of camouflage, sandbags in heaps, told us where we were. But they were far less noticeable than they had been from the railway. Our eyes commanded a wide stretch of country, sweeping away to the horizon. For miles all around the air was pure and sweet, and the horror of Thiepval seemed far behind. We saw nobody at all and it was hard to realise that so short ago this had been a battlefield for thousands. Only a lonely cross here and there – or a group of crosses – suggested it. I had begun to fear our American had forgotten all about us and was prepared to carry us to the end of the world when all at once, in the centre of the champaign and at its crest, he stopped. ‘This is [Vimy] Ridge,’ he said, ‘I’m going on to Lens. Goodbye.’ Hardly waiting for our thanks, he whizzed off and we were alone.

The high ground of Vimy Ridge provided a natural vantage point of great military significance. In April 1917, as part of the wider Battle of Arras, the Canadian Corps succeeded in winning the Ridge from the Germans at the cost of over 10,000 casualties.

The silence was unbroken; the land was desolate. Almost afraid to break the quiet, we moved on to the grass, and with a cry of delight, I stooped down and picked a flower. It was the commonest little yellow thing, that grows in unnoticed thousands at home, but I held it reverently and greedily and the Hut Lady looked at it too. ‘Isn’t it lovely?’ she said lingeringly, stroking it petal by petal. To find a flower after all that we had seen, seemed a miracle.

We moved on and picked up bits of shells, bullets, stray bits of camouflage: all the odds and ends left over from the fighting.

‘Come, and I’ll show you a big gun emplacement – boche,’ he said, changing the subject, ‘and then we’ll look at the Canadian memorial.’

My eyes had turned to the horizon again, to the heights that once were St Eloi. Someone I knew lay there, who had been a Canadian, and it was too far for me to go. I could only see the Ridge where he had been killed, and not the place where he lay.

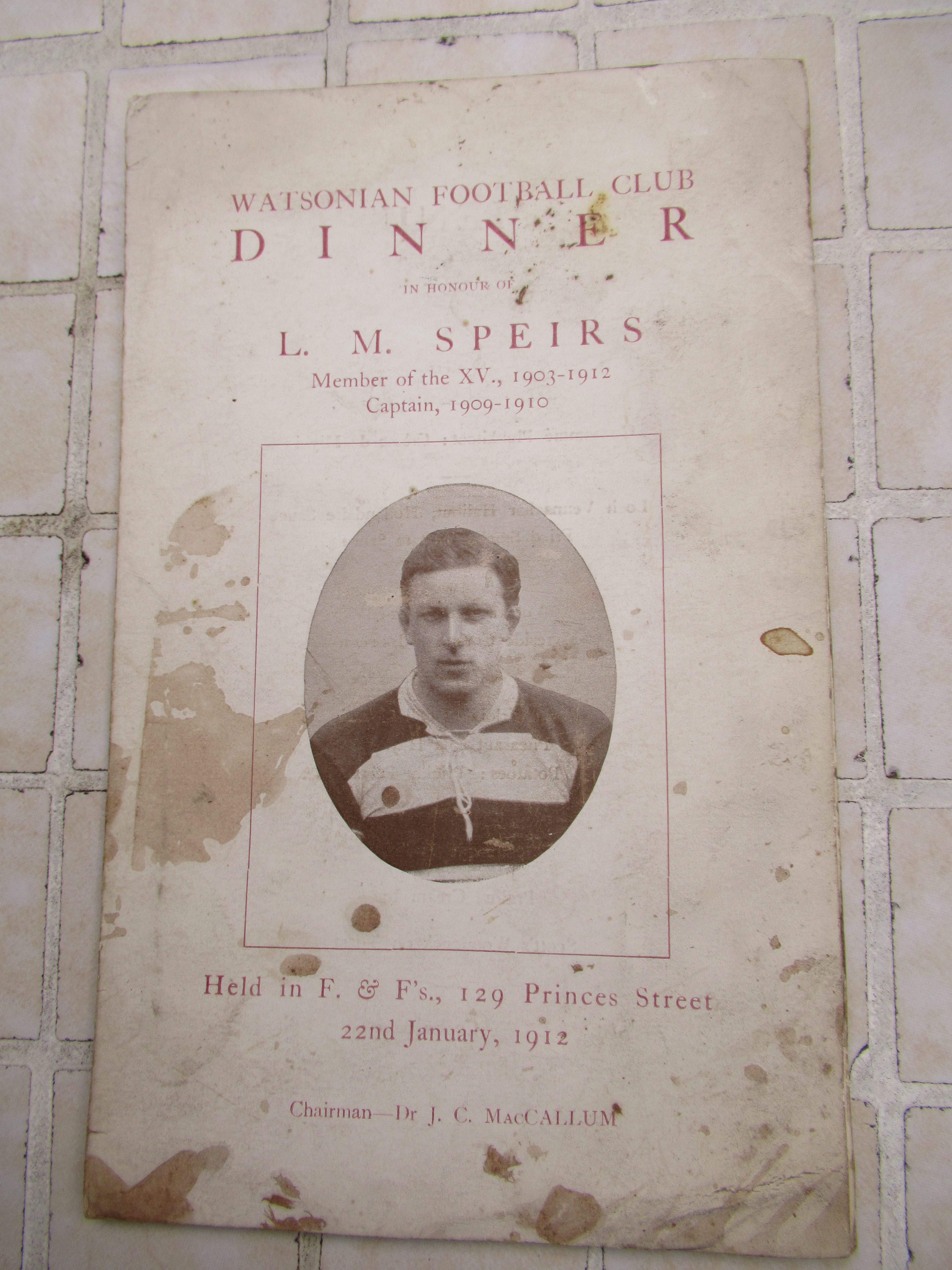

As Christina looks towards St Eloi, we have a rare insight into her personal experience of loss and grief during the war years. The soldier in her thoughts is Captain Daniel Gordon Campbell of the Canadian Infantry, who had been engaged to marry her sister Louise. He had grown up near the Keith family, in Halkirk. Like them he attended the Miller Institute and Edinburgh University, where he excelled both academically and at sport, representing Scotland at the high jump. A lawyer, he had emigrated to Canada, and was serving with a Canadian regiment when he was killed at Vimy Ridge on 9 April 1917. He is buried in the cemetery at Mont St Eloi. Louise was devastated by his death, and kept detailed scrapbooks which include newspaper cuttings about the Canadian action at Vimy, letters of sympathy from friends, and information about his final resting place.

I went quietly to the big gun emplacement. It seemed untouched, and even to my inexperienced eyes, of amazing strength. ‘We got held up here I don’t know how long,’ he explained, ‘you see how well it is screened and how it commands all this stretch of ground.’

‘Put down those things you’re carrying,’ he said, glancing at my armful of spent bullets, bits of camouflage, bits of shells and flowers. ‘No-one will touch them here and I’ll snap you at the foot of Canada’s cross.’

The great high cross, with Canada in white letters, stood high on the crest of the ridge. The bright March sunlight danced on the white letters and picked out with silver the grey cross. The keen March wind blew like the winds of home over all the quiet field. The Hut Lady and I sat in the shadow of the memorial and looked towards St Eloi.

I have never seen the snapshots for, though our officer carefully took our names and addresses down on our map, he forgot to send them.

Today Vimy Ridge is the site of the breathtaking Canadian National War Memorial, overlooking the landscape on which so many Canadians lost their lives. More than 11,000 names of those whose grave is unknown are inscribed on the walls of this impressive monument, which was unveiled in 1936. However, even while the war was still continuing, memorials were erected on Vimy Ridge to commemorate the devastating losses suffered by the Canadian troops. Christina and her friend were photographed at the foot of one of these memorials. Louise’s scrapbook contains a photograph sent to her of one such cross, which may be the one visited by Christina.

Edit:

Daniel Gordon Campbell is among the lawyers featured in this exhibition in Toronto. It’s good that he is remembered.

© All content copyright Flora Johnston. You may reblog or share with acknowledgement, but please do not use in any other context without permission.